I was ready to check out from one of two places: Vegas, or life

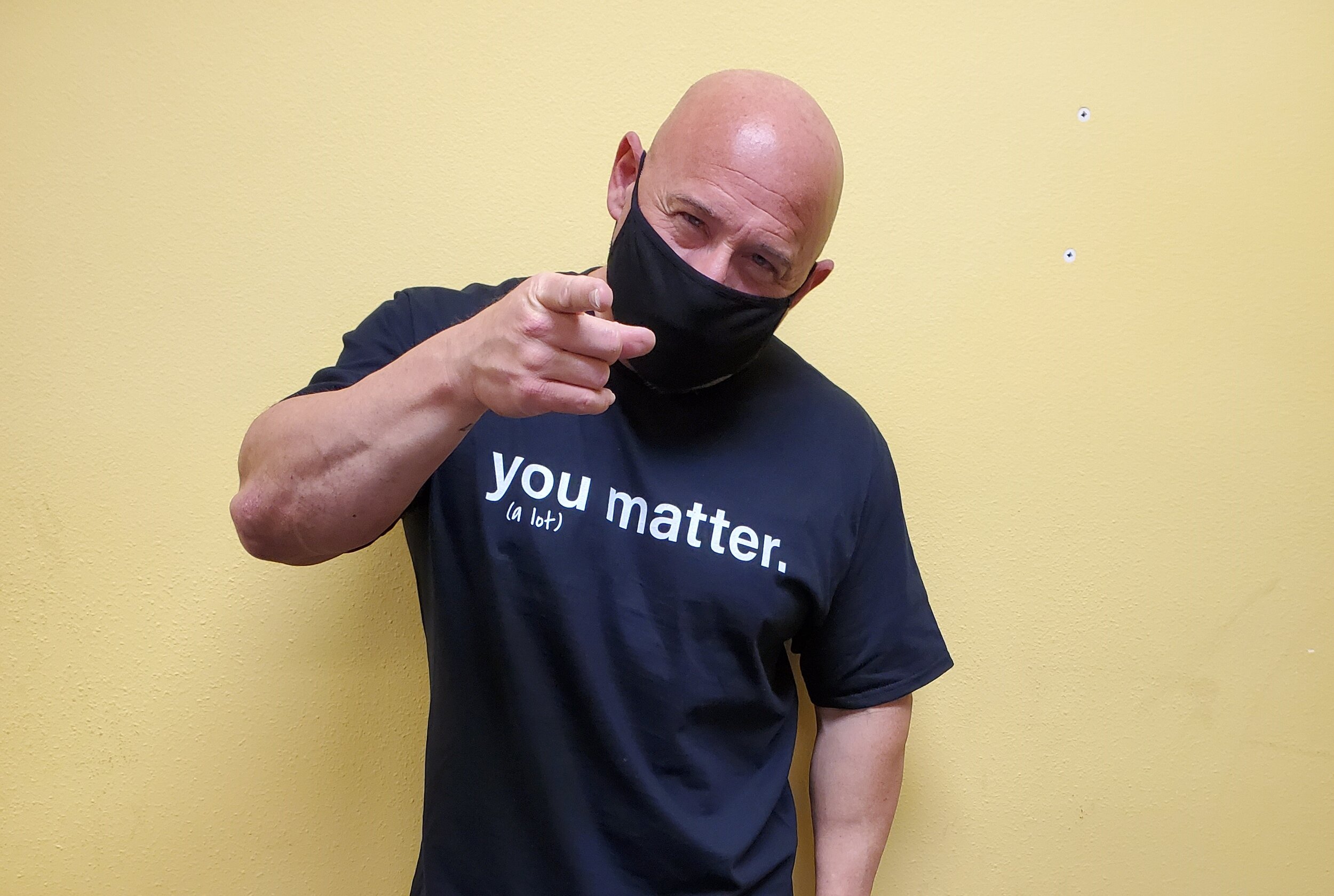

Professional sports in Las Vegas helped heal depression and suicidal thoughts, albeit both still an uphill battle, as a spors-writing career was revitalized. (Photo: Veronica Regnault)

LAS VEGAS — I don't remember the first time I thought about committing suicide, it was that long ago.

But I do remember the first time I felt comfortable talking about it.

The Vegas Golden Knights had clinched a berth into the 2018 Stanley Cup Final, and I had felt my career took a turn for the better.

Three years prior to that, however, I reached a point in my life I had been through enough, and seriously thought about checking out from one of two places: Las Vegas, or life.

Fast forward to 2020.

I still get those "if I wasn't here, things would be much easier" thoughts - daily.

Some days the thoughts linger; other days I push them aside. The most important thing I've learned is refusing to shelter those emotions. Instead, I talk about them. I am up front about cerebral health.

I remind others it is okay to not be okay while doing my best to inspire others. I send random text messages to people I haven't spoken with for hours, days or months to remind them they matter. I do whatever it takes to make sure I am talking about mental health on a daily basis because it is relevant.

On Nov. 12 I saw a tweet that said suicide figures are up 200% since COVID lockdown. Whether or not that percentage is accurate, it's become quite alarming how this pandemic has devastated people's mental game.

Which is why frequent conversation on the subject can be an alarm clock that wakes me up to the reality there's a part of me that is not okay.

And I'm good with that.

OFF THE LEDGE

Soon after my son graduated high school, I wasn't sure what I wanted to do. I felt I had done my part, raising him jointly with his mother in the best co-parenting partnership God could've blessed me with from the day we split during the week of his first birthday. Though I failed at the most important relationship I'd known to that point, I vowed to make sure I wouldn't fail at the second. I wanted my son to have what I never had, a father who wanted to be involved in every aspect of his life, giving him the opportunity to participate in whatever it was he was interested in, supporting him every step of the way, and teaching him some of the most important values I tried to live by.

Once he turned 18, the job was done. Let me be clear, the teaching never ends, but raising your offspring does. And my job was complete.

Problem was, I abandoned a career as a sports journalist to be the best single father I could possibly be, and found myself scratching and clawing my way back into an industry that was filled with a new brand of journalism, one littered with a different wave of ethical traits and personalities. I wasn't completely out of the game, as I had tried to stay relevant by filling in where I could for random freelance assignments over the year. But never on a daily basis. I was entrenched with being a father, and by working for an independent sports-betting group, I was able to work from anywhere on the planet as long as I had a laptop and could get online.

When my son got his driver's license in 2012, it opened the door to start freelance writing again. A longtime friend made one phone call and I was introduced to a local news editor with The Associated Press. I auditioned at a UNLV football game and was added to the local roster. Eventually, I moved up the ranks and routinely was assigned to events, covering everything that came to Las Vegas. I was convinced I was destined to resurrect a career that began in 1987 with the state's only Black newspaper.

And while I did, sort of, I really didn't.

The assignments began to increase; job offers didn't - neither locally nor nationally. I couldn’t even get an email or phone call returned from people I knew personally after they told me to apply for jobs. My ego was shot. My mental game took more hits than a quarterback with a rookie offensive line, and bouts with depression increased.

In 2014 and 2015, I told several people I was open to moving away from Southern Nevada if it meant being able to find full-time work, and get back into the passion I'd had since meeting Brent Musburger in 1977 and getting his autograph after telling him I watched him on NFL Today every Sunday. I mean, him and Howard Cosell were it for me. I was convinced at 7 years old I could do play-by-play for Monday Night Football.

But at 45 years old, my thoughts began drifting into abyss, knowing my son could be financially secure before the ink dried on my death certificate and he could pursue his dreams in the fitness industry. I may not have had a bottle of pills waiting in the bedside table, or a bullet in the chamber with my name on it, but the mental anguish kept my brain stirring with revolting thoughts.

Then, one person took the time to actually talk to me, talk me off a ledge he never knew I was ready to jump from. Las Vegas columnist Ed Graney began encouraging me about the complexion of professional sports in my hometown. We shared several conversations, and one day - before there was any official announcement - he assured me the NHL was coming and it would be the start of Las Vegas as a hotbed for pro sports. He implored me not do anything drastic. In his mind, drastic meant leaving town; in my mind it meant leave life.

I believed him because there was a part of me that sensed he believed in me.

That was the journey I struggled with.

ACE IN THE HOLE

Las Vegas Aces All-Star Kayla McBride: "Mental health isn't a game that you win or lose - it's a journey." (Photo courtesy: Las Vegas Aces)

When the Golden Knights arrived, I was thankful every time I made that walk from the parking garage to press row inside T-Mobile Arena. Not just because I was covering history in the making, but because my life felt worthwhile again. Days before Game 1 of the Stanley Cup Final, I thanked Ed and several others on a Facebook post, marking the first time I revealed publicly I struggled with mental health issues and entertained suicidal thoughts.

"The impact they have had on the (National Hockey) League is certainly 'the stuff of legend,'" Hall of Fame broadcaster Mike "Doc" Emrick wrote to me in an email shortly after he announced his retirement last month.

Imagine, I was second-guessing my existence in 2015, covered the 2018 Stanley Cup Final, recently sat in the same press box to cover the first NFL game in Las Vegas on a Monday night with the same Musburger whose autograph I still have in my childhood autograph book, and now, a personal e-mail conversation with Emrick.

The impact the Golden Knights had wasn't just on the league Doc, they helped close some wounds on a personal level.

And they're not the only ones.

"Mental health isn't a game that you win or lose," Las Vegas Aces All-Star Kayla McBride said this past season during a Zoom session. "It's a journey."

McBride, whose own bouts with mental health were chronicled in a wonderfully self-penned article in The Player's Tribune, said it best. And we're talking about one of the toughest athletes I've ever covered at any level - mentally and physically, as it turns out.

There's always been this rough edge to her, stand-offish if you will. As I look back, I believe I have an idea why. She's never denied me a conversation, and we've shared some laughs. But she is cautious of opening up when it comes to anything outside her game. McBride could be 1-of-15 from the floor, and she'll say she needs to work harder. Off the court topics, she can be guarded. I noticed it the one time we sat baseline at Mandalay Bay Events Center after a pre-game shootaround and discussed her upbringing in Pennsylvania.

I didn't place it then, but as I read her story, I immediately pictured the pain in her face, her words, and her eyes that day. I didn't know then. I realize it now. It's pain she's always endured and fought through and keeps her mind stirring, the same way mine has done to me so many times.

They say you never know what someone is going through, and you should never judge. I've never judged McBride, but I think because she's been one of my favorite athletes to cover since the Aces moved here from San Antonio, I appreciate and understand her battles a little more now.

I've been a mental health advocate since that Facebook post prior to the Stanley Cup, and I've tried to inspire people on social media. Golden Knights goalie Robin Lehner revealed his struggles and Raiders tight end Darren Waller is a recovering addict. But it was Kay Mac's article that hit home for me. I've read it several times. Leading up to writing this, I read it once a day - yes, that impactful for me.

I have never sat down and actually talked about anything in regards to my mental health in detail, other than with a family therapist.

I still haven't, really. It took me forever to get this far.

But hey, some dap and a hug to Kay Mac, because she has no idea how much her article and candid Zoom sessions this past season helped me.

"Athletes aren't invincible and I think having that conversation, it normalizes us and humanizes us," she told us one day. "And it's something that a lot of us struggle with, and I think talking about it helps."

Indeed Kay Mac, indeed.

KEEPING IT REAL

It is important to remind others it is okay to not be okay and that they matter. Do what it takes to discuss mental health and suicide issues.

I no longer worry about what people think when I discuss mental health, depression, or suicide awareness.

What I do worry about is the same year I revealed I was dealing with mental health issues there were 1.4 million suicide attempts, that 48,344 Americans died by suicide, and that suicide was the 10th leading cause of death in the United States.

I'm beyond thankful I was able to open up at therapy many years ago when the goal was to become a better husband and stepfather. Unfortunately that part didn't work since I came home to a half-empty house and dropped to 1-for-3 with the three relationships that have meant most to me. But it was my continued therapy that helped me dig deeper into my childhood and teen-age years to uncover a lot of pent up resentment and painful occurrences that triggered my mental health. Those are for an entirely different column that I'm confident I'll be able to talk about publicly one day.

Those extra therapy sessions educated me on how to delve into the mental process of flipping the script on bouts with depression. Normalizing battles with mental health and suicidal thoughts by talking about them regularly is like keeping the IV drip clear. You never want that getting clogged, the same way you cannot let your brain overload with negativity.

I've been through days where loyalty has overcome fake friendships and received screenshots of group messages on social media, or text messages, where people I believed had my back were actually stabbing it. My emotions - anger, frustration, fear, sadness, rage - were all challenged. The best was accidentally receiving a message I wasn't supposed to from a media member talking trash. I've learned to control my thoughts much better, and would much rather engage positivity.

I try to keep it real, in an old school manner, without engaging old school ways of handling things. I remember running the streets of Las Vegas in the mid- to late-1980s, running my mouth to the wrong people and catching a swift backhand to the chops, shutting me up quickly. But that's simply not the way to handle things in 2020. You learn who you can trust.

I will never tell anyone they shouldn't have certain thoughts and shouldn't think the way they do, because I for one know what it's like to be blindsided with depressive days. You don't avoid them; you learn to control them once they hit. I refuse to believe medication will help, unless of course you're clinically diagnosed with, say, bipolar disorder like Lehner and need chemical balancing. But to count on drugs to reverse depressive or suicidal thoughts, in my opinion, will only suppress them - not rectify them.

You learn that mental health is dark and friendless, as are thoughts that are left unexpressed.

Which is why it is important to talk. And talk.

And talk.

It's what Kay Mac reminded us all that day on Zoom, that this isn't a game you win or lose - it's a journey.